MY GENEROUS FRIEND, TREE

Sepideh Parand

Crafting in nature

I would like to acknowledge and thank the Coast Salish Nations of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish), and səli̓ lw̓ ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh), on whose unceded traditional territories we teach, learn and live.

I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Louise St. Pierre for her support, her patience, her motivation and her knowledge. I could not have imagined having a better supervisor for my master studies.

I would like to thank my internal reviewer Brenda Crabtree. Her work inspired me and her guidance improved my research.

I would like to thank my classmates and all the teachers who supported me in these two years. Seeing them and talking with them was my motivation.

I would like to thank my family, my parents and my sisters, who support me spiritually and my dearest husband who always has stood by my side and has helped me. This research could not have happened without him.

Last but not least, I would like to express my gratitude to nature. She has been my teacher through this journey. She gave me her materials, and showed me the path. I have spent joyful times, making with her.

To seek my roots, to become one with nature,

I make in the land, and her beauties immersed me, I see with her eyes.

I will find the true me, the one who is in symmetry with her surroundings.

I want to keep nature safe because I can feel the trees’ happiness when it rains, and I can

feel the wind blowing through the grass’s hair.

I will share these stories with my children, and they will see and feel them as I do.

Abstract

Although humans are a part of the natural world, the relationship between nature and humans is not fully understood. The earth is damaged by humans, and the resources of nature are being taken for granted. Humans cannot survive without nature, but nature can survive without us.

In this research, the relationship between self and the natural world is studied through the method of crafting. For me, this led to finding a spiritual relationship with nature, and positioning myself in greater harmony with her. Crafting is a relational practice that connects several aspects of my research, such as materiality, the positionality of the maker, relationships with other people and the generosity of nature. Crafting with nature as a method led to discovering deeper aspects of that relationship, such as spirituality and reciprocity. Moreover, by practicing land-based making in my everyday life, concepts like gratitude, animacy, and agency of the more-than-human world have become more tangible to me. I call the objects that are being made my makings. My makings are not the ultimate goal, but making them was a way to gain philosophical insight. The purpose of this research is not the form and beauty of the objects. It is how crafting helped me as a maker to find my place in relation to the natural world. Therefore, you can see that I made a variety of objects based on the materials that I had, the techniques that I wanted to experience, and the place that I wanted to make in.

My research is a personal journey. This written thesis is mostly a meditation on my relationship with craft and nature. At the end of the thesis, I offer suggestions for others who might be looking for a relationship with nature through craft. I hope this helps others create their own rituals and gain a closer relationship with nature.

Sustainability, Spirituality, Nature, Craft, Making.

Preamble

I am writing this letter to all the trees. I cannot choose my favorite because I think you are all beautiful, especially when you are standing together.

Hello my generous friend, Tree

I feel Sohrab Sepehri understood you when he wrote;

“I haven’t seen two poplars to be enemies.

I haven’t seen a willow selling its shade to the ground

The elm tree freely bestows its branch to the crow.

Wherever there is a leaf, my passion blossoms.

A poppy bush has bathed me in the flow of existence” (Sepehri)

I have a lot to learn from you. I wish I could be more like you. I could take care of the earth by only existing and being alive. I hope I could be pure like you. It is like Kimmerer (2013) said Sometimes I wish I could photosynthesize so that just by being, just by shimmering at the meadow’s edge of floating lazily on a pond, I could be doing the work of the world while standing silent in the sun. (p. 176) I will sit by you every day to understand you more. Like a good friend, being with you will have a good influence on me.

I know you as my sister. We are all the children of mother earth. Now I understand why they call her the mother earth. Because she takes care of all beings without any expectations, she provides for the well-being of us like a mother. I shouldn’t forget that I am a part of her, and my life is dependent on hers in many ways. So, like a good child, I should try for her well-being too.

We humans are takers. But it doesn’t mean that I can’t make changes in how I use nature’s gifts. If I am a consumer, I can consume more responsibly. I should consume in a way that honors the lives that I took and resources that I used, and give my gratitude to them. I remember my grandmother always had a bucket in her sink to save her wastewater to water her garden. The elderly woman with her curved back was having a hard time carrying the bucket to the yard, but it never occurred to her not to do that. And here I am, two generations after her, trying to do what she had taught me. Back then, I was grumbling that she didn’t take care of herself, and complaining when she made me carry the bucket, but now I understand how thoughtful she was, and what a great example she was for me.

With the example of Mother Nature and my grandmother, I will rise by your side to remind people to change how they see the world and to take our elder teachers, the trees, as their role models.

Stay green,

Your loving admirer,

Sepideh

Ps. I am so grateful for your fellow Tree’s wood that I use. I try my best not to waste them, and I will tell their stories to share their soul with people.

My story

Everything started two years ago when I came to Vancouver, this beautiful city. I come from Iran, a country where our bad habits and behaviors have damaged nature. Most towns in Iran suffer from a high level of air pollution. There is a vast range of deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and pollution caused by garbage. When I saw Vancouver’s beautiful environment, I felt a strong urge to protect it. I became interested in sustainability and started my research into natural materials, reusing, and recycling materials. I work in a retail design manufacturing company where they use hardwood, plywood, MDF board, and leather. I see how their waste materials can be a valuable resource for a maker like me. There are several bins for leftover materials in the workshop next to the cutting machines, and when they get full, they will be unloaded in a large central dumpster outside the company. I search in the waste bins and collect pieces of wood and leather. I try to take anything that I want before they are moved outside and being left in the rain. There are other people working in the company who use these materials. They use it for personal projects or even for burning it in their fireplaces. The company has an interesting policy that lets us use the woodworking machinery, place, and waste materials after working hours or on weekends for personal projects. It reduces the amount of waste, but the waste that is being made is more than that. I have opposite feelings about the waste bins. I feel a kind of shame to see this huge amount of waste. On the other hand, the maker inside me is happy to see a lot of free materials that can be used in her future projects.

Because Vancouver is a multicultural city, I could see and learn a lot from different people and different cultures and crafts. By reading Indigenous knowledge (Kimmerer 2013; Kuokkanen 2006; Simpson 2014) and thinking about this as I explored land-based practices, I learned the ways of being in a spiritual connection with nature, and how to respect the land in life and in art and in craft.

My mind, hands, tools, materials, and even my environment are like a connected network. I am studying the effects that my connection with nature has on my makings. The connections are happening in three ways: When I use materials from nature; When I get inspired by nature; When I make artefacts in nature.

As I will talk about later, these ways of connecting with nature helped me to find my daily rituals of crafting with nature. For me, these led to a spiritual relationship, a relationship of kinship and humility. This has helped me to learn ways of living in harmony with my surroundings.

I believe nature has agency and that I can learn from her when I spend time with her. I learned about how making and crafting can affect our well-being and confidence, how a maker can reach self-actualization through making, how one feels a sense of connection with a handmade object, and how someone feels a sense of belonging to an object that they made themselves.

Intentions

“Biodiversity – the rich diversity of life on Earth – is being lost at an alarming rate. The impacts of this loss on our well-being are mounting” (Date World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report). We are dependent on the natural world for every aspect of our lives, from food and water, to medicines for our body and our soul.

We can see that many designers are responding by doing projects related to protecting and renewing the natural world (Fletcher et al., 2019). I count myself among these designers. I am doing my share by finding a deeper connection with more-than-humans and the Earth through the practice of craft.

In discussing the history of designing with nature, Louise St. Pierre (2019) talked about how respect for nature became diminished during the scientific revolution and was mostly lost by the time of Western modernity. She notes how the Arts and Crafts movement used nature as inspiration for decorative form and love of nature was a temporary passion. Mechanistic understandings of ecology influenced the Bauhaus, and many other designers in the 20th century. Nature was modified and manipulated for mankind’s pleasure. Later, more organic and fluid understandings of ecology lead to design practices like bio-design and biophilic design, but the idea that humans can control the natural world continues. She advocates practicing humility and spirituality to develop relationships with design and nature that bring awareness to our vulnerability and interdependence.

I am searching for ways to build on this, to develop a reciprocal relationship with the land—a relationship with symmetry and harmony so that people and nature both benefit. The Art and Craft movement, led by William Morris in the 19th century, has influenced my work. “They rejected mechanical production and the mechanistic thinking of the industrial revolution. Their work was passionate and emotional” (p. 94). Citing Pevsner, St. Pierre goes on to say that they were “Inspired by close study of nature” (p. 94). Like Morris, I am mimicking nature in my works, and like biomimicry I am inspired by nature’s ideas. But, unlike others, I have an intention to engage in deep understanding with nature. I believe my research is sitting in the context of spirituality. I cannot ignore the fact that I am living in British Columbia, and I am getting to know more and more every day about indigenous ways of knowing and learning from nature. I am connecting to nature through close study. I mimic nature; I explore her materials to get to know her better. To make a deeper connection with her, to learn to talk with her, I create stories and objects to care for her. The embodied practice of being with her through every day crafting gives me the most joy with her. This is my

spiritual practice.

There are some moments and some experiences that stick to one’s mind. When I was working in our little workshop in Iran with my husband, we used to work with pine wood. The knots in pinewood have a strong smell. Sometimes, in the process of joining and planing, knots fall out of wood in the shape of a small cylinder. I remember Mehdi giving me the

knots that were falling out, and how I kept one in my hand for hours and smelled it. Now every time that I think of any wood, I remember that fantastic smell. In my mind, wood is the color of walnut and the scent of pine. During my research, and my search for an embodied connection with nature, I am trying to create a strong image of nature like the experience that I had with the smell of pine in my mind. I believe memories and joyful experiences play an essential part in my connections.

St. Pierre, in her recent book, says, “The spiritual view of design and nature involves attending to the kind of connection with nature that emerges from the awareness of ourselves as but “one manifestation of a web relationship which encompasses everything”” (citing Bai, p. 105). So, I am doing this research by visiting nature and making with her. In this process, I know myself better. There is a quality in nature that makes me want to be a poet. It brings up my deepest emotions, and that makes me know myself. I learned my potentials, my desires and, my concerns. My goal was to bond with nature in this project, but I am gaining something more valuable. I am learning the way of living in symmetry with nature.

This is a journey of discovery based on my passions.

Manner of making

This thesis is about my journey of learning to connect with nature. It started with admiring nature to find out how much nature offers, and how much she can teach me through every aspect of everyday life. This journey led to finding a spiritual connection with the land and finding deep respect for her. I seek sustainability, not because of the musts, but because of the love and care I have for nature.

Fletcher (2021) uses life writing as a research method to unfold the relationship between human life and more-than-human nature. She uses this method as a self-reflective activity to reach an awareness of herself. She witnessed the effect of places in her writing, and she states that life writing helped her to know places better. I feel that I know this method and have experienced it, except my language is the language of making. Fletcher uses words as her material. My materials are from nature. I tell stories of nature and places through my making with my materials – my crafting. I chose making, because I think making is a universal language that allows me to share my stories with everyone who might or might not understand my words. There are qualities in craft: the touch, the form, and the details.

These can tell half of the story.

In the age of ecological crisis that we live

in, any kind of creativity that strengthens

the capacity of care and makes a bond of

solidarity between humans and the more-than-

human world is valuable. I came upon

a methodology that suits my personality the

most. It contains rapid making and reflecting .I am fully engaged with experiencing

materials and learning new skills. I found

my two passions: making and nature. I followed

them both.

I remember in the beginning I was nervous

about my research. I didn’t know how to

start, and I was missing making. I could not

find a way to relate my passion and skills to

my research. My supervisor asked me, what

gives me joy? My answer was walking in

nature and making. She suggested that I go

out for a walk in nature regularly, observe,

collect and then come back to the workshop

and make. I was so excited.

I cannot forget my first visit to nature. All my senses

were focusing and absorbing. Somehow

with practice, it became a habit to pay more

attention to the details of nature when I

was walking, like listening to your teacher.

Blenkinsop & Beeman (2010) write about

nature as teacher. They talked about “meander

knowing” (p. 32), the knowledge that

comes from listening to what the land is trying to tell us. This kind of learning happens when we are not trying, when we are meandering and letting things be.

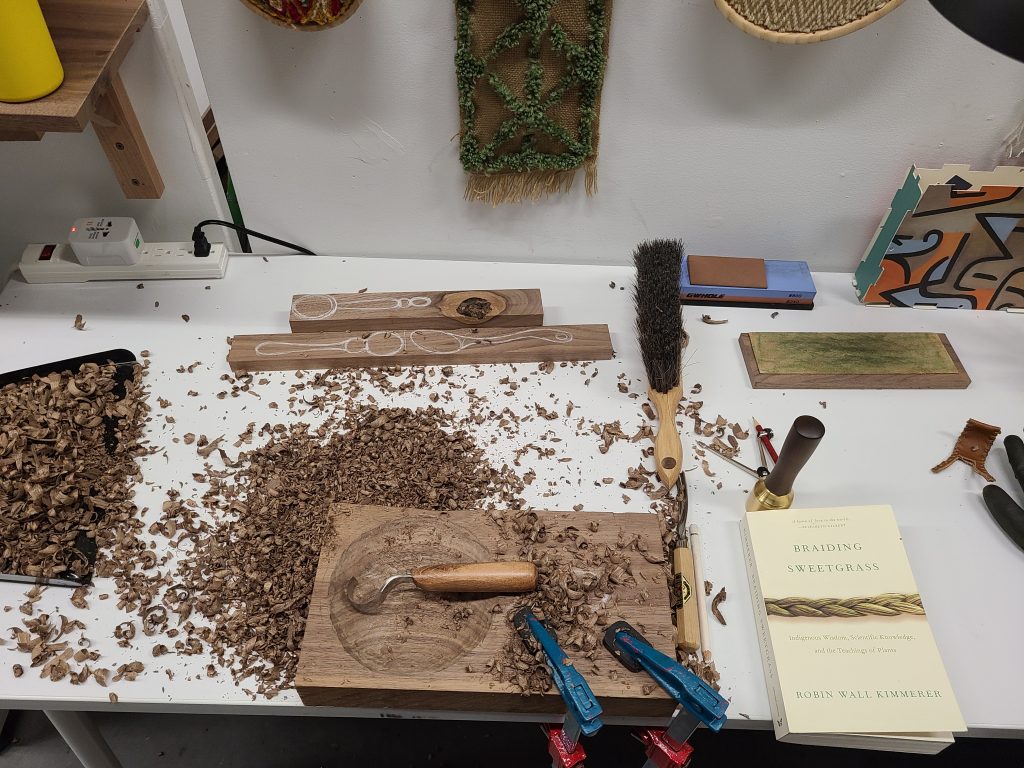

In the transition between walking in nature and then going back to school to do my making, some information went missing, some memories or senses were forgotten. So, inspired by Camozzi’s (2019) Earthbond Prototyping, I started to make in nature. I start with a walk to embrace the feeling of joy in nature, carrying a knife and a piece of wood in my bag. And I end my walk by sitting by a tree and making. In the process of making, mostly my hand is doing the job, not my mind. I let my hand make freely. It means that most of the making is done without planning. I let the material tell my hand what to do. My mind comes along afterwards to reflect on the making, to observe, and sometimes to critique. I mostly find out the connections, the reasons, and the tendencies after something has been created, by reflecting on it later.

To give meaning to the makings, I take nature as my participant (see also Blenkinsop 2010; Fletcher 2019). Sometimes the participation shows itself in a form, sometimes in a color or a pattern, or even in the kind of material that I use. Seeing nature in form, color and material is tangible, but the intangible participation with nature is about my mental and emotional connection. It is about the feeling that I experience when I make in nature, like the bond I have with the tree I remember from my childhood. When I was a child, there was a mulberry tree in front of our house where I played all the time. She was a big and beautiful tree. I enjoyed her shadow and her fruits. I remember I was afraid of heights, but I used to climb a ladder to go on the garage roof to eat her berries. We moved from that house when I was eleven, and the thing that I missed the most about that house was the tree. When I sit in the shadow of any other tree or when I pick fruits of any tree, I think about her. The memory of the mulberry tree and the connection that I had with her as a child helped me in this research process. I wonder if the tree knows me the way that I know her. Stuckey (2010) told a story of being known by a birch tree, and she inspired me. There are other ways of knowing and being known. I like to think that the mulberry tree knows me as well. I want to think she missed that little girl that used to play by her side every day and couldn’t wait until her sweet fruits became ready to eat.

To share these experiences with others, I make some gifts. It is a kind of appreciation. Sometimes I give them away as an exchange for someone else’s art, so these gifts contain lots of stories and meaning. I try to make gifts with a metaphor in the form of a shared experience or memory. It gives a playful quality to the artifact. It is a way of making a meaningful connection with people and sharing my experiences and stories. It is another aspect of relationality in my craft.

In reflecting on my makings, I write about the experiences, the feelings, and the intentions I had before making them. Then I question the artifact. Does it remind me of the feelings that I experienced when I made it? Is this something that others can sense, or is it an inner feeling specific to me? How can I make it better? What did I learn while making it? My ritual is something like this:

A walk in nature,

Sitting with a tree,

Making in nature / Or bring back memories and senses to the studio and do the making,

Setting aside my thinking mind, and letting the material and my hand do the work. This

allows the agency of materials.

Reflect on how nature talks through my objects,

Ask questions of my objects.

This ritual is not something fixed. I may or may not do all the steps every time. Sometimes some of the steps might be as simple as a thinking before falling asleep. I will not let the obsession of doing something precisely as planned stop me from doing it at all.

Overall, my methodology is my ritual for connecting myself to my crafts and nature. I feel an urge to share this lovely practice with others. So, later in this thesis, I describe this in detail as an offering to others about how to connect with nature.

Practices

Storytelling

“In winter, when the green earth lies resting beneath a blanket of snow, this is time for storytelling” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 3).

Stories can accompany the time that I spend on making. They might be the stories of the inspirational people that can lead us through our work, or stories about beautiful and peaceful thinkers who teach us how to be kind to our land. There are even stories about the creatures one makes in one’s mind and then makes with one’s hands. How will these makings continue living on the earth, and how might they affect the environment? How might they affect other people?

The story of my conversation with leather.

I was in my studio space, sketching my next wood project. I asked the wood, “What do you want to become?”

He said: “Make me something beautiful, let the world know I used to be a tree and living in a dumpster for a while doesn’t make me less. I am beautiful and worthwhile. I used to be a shelter for the birds and a house for squirrels. I used to make shade for you. Make me in a way that everyone sees my strength and polishes me to show my color and pattern.”

I heard something moving. It was the leather that was trying to come out from under a pile of stuff under my table. Leather cleaned the dust from herself, looked at the shelves full of wood objects, sitting there, gorgeous. She harrumphed and said: “what about me? I had a life before being leather. I used to live on a farm. I was the close friend of the bird and the tree. Please make me alive again and give me a purpose to continue. Let me sit next to my old friend wood again.”

I told her: “I afraid that you do not fit in my research. I am trying to find a way to be more kind to nature, but by using you, I am saying that putting human needs on top of other beings is ok. “

She realized that I was avoiding her; “I was waste anyway. My meat was used, and the skin was the waste. Isn’t it better to use it for something? Besides, I am available to you, and using me is an act of gratitude. Let’s celebrate my life and my value by getting the most use out of me.” she replied.

She was right. I wasn’t acknowledging how valuable she is, and I have to cherish her life by valuing her.

Now months have passed since the time that the leather talked to me. I put leather next to her old friend, wood. She gives a new look and energy to my artifacts. Understanding the availability and life of materials like leather is so important to me. I am happy that she talked to me and showed me a new way.

Reflecting on the story of my conversation with leather made me realize that even though I am trying to say that all beings –plants, animals and, humans–have equal intrinsic value, deep down, I give more importance to animals. I asked myself, what is the difference between wood and leather? Why am I worried about the animal more than the tree? I realized that I see the animal a sentient and the tree as a non-sentient being. It comes from the false

impression that there are hierarchies in nature.

“In Potawatomi, rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places. Beings that are imbued with spirit, our sacred medicines, our songs, drums, and even stories, are all animate” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 55). The language of animacy is the language that helped the Potawatomi people to learn the real value of every being. A potent reminder in every word that they say.

Learning at my mother’s elbow

When I was a child, my mom used to knit clothes. I was fascinated by how she would knit a piece from yarn. Like any curious child, I wanted to help. So, she taught me the easiest thing, how to make crochet chains. I used to make long, long chains with my mom’s scrap yarn.

And here I am after more than twenty years using the same technique to knit a story on a loom. I love that I can take the lines everywhere I want on the loom, twist them, move them around, and change their colors on the way. It is like a transparent frame of memories, joys, and needs. It is a story of me in the city of blue skies and endless oceans, seeking my childhood memories of making with my mother. She taught me my first lessons about making, and I am doing what I do because of her.

Somehow in my research I use intergenerational learning that passed to me from my mother and my grandmother. The passing of knowledge has a close relationship with crafting. There are skills that one learns best within a close relationship between a master and a student, a mother and a daughter. Lave and Wagner (1991) call this kind of learning “situated learning”. It is the kind of learning that a person gains by being situated in a community and learning

in an ongoing environment in relationship with others. Mackinnon (1996) calls it “learning at the elbows” and he describes it as learning when situated in a close relation with your teacher. “Through work in classrooms at one another’s elbows, teachers and teachers-to-be influence each other’s practice” (p. 665). I learned knitting at my mother’s elbow. This learning had such an influence on me that I think of her every time that I knit. I may gained more experience in knitting by myself through the time, but I know her as my first teacher.

Crafting

At some point, my crafts were telling stories. That was when I had opened my heart to my surroundings and let my feelings move my hand to make something. It was an act of creating at the moment without overthinking. Actually, I was thinking with making, an act of putting a mark on material based on what was happening deep inside of me. Richard Sennett (2008) argues that “making is thinking”. He explores the effects of craftsmanship as “an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake” (Sennett, 2008, p. 9). Maybe, for me, making is like meander knowing.

Hand-made objects and machine-made objects

I want to look at the ethics of the things that are being made differently. When I compare handmade objects and machine-made objects, the makers can express themselves in the making with hand. They can be creative and learn skills in the process of making. These actions bring joy to the maker and make them confident.

On the other hand, in mass production with machines, the person who operates the machine is only overseeing the job of the device. The operator can’t learn as much, and they will be trapped in a loop of repeating jobs. In many cases, the operator doesn’t even program the machine.

Yanagi and Leach are the authors of the book “The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty” which was first published in 1972. Yanagi was known as the father of the Japanese craft movement. They argue against mass produced work “because the workers have no outlet of expression and the products are heartless” (p. 107). They say the machine works are standardize and cold.

On the other hand, they talk about handmade objects: “There is something so basic, so natural in the hand that the urge to utilize its power will always make itself felt” (p. 107). they state that the special characteristics of handmade objects always find its way to human hearts.

I know that when I use machines for making it’s not comparable with what is being done in mass production. There is always an impulse when I make something with the machine, to at least put some traces of hand on it. That’s why I carve on woodturned bowls, add woven leather onto wood boxes, add stitches onto leather, and weave my own tufting cloth. I loved the hand-woven background of my tufting so much that I couldn’t cover it with tufting. I like the hand-woven background and the tufting to be next to each other.

Weaving in the frame of bowls

The city put on bright yellow, orange and red clothes. It is a perfect time for wandering on the streets and watching.

I make a couple of bowls in the workshop, and I think this time I would do a different thing with them. Maybe they could be a frame for weaving.

I feel confident about the previous looms that I made for myself. One of the things that I always remind myself is too much making is never too much because I will learn in each process, and I will be inspired and prepared for my next experiment.

I put holes on the edge of the bowl to string the threads and make my loom. I choose a sunny day to go out and continue making. I go to the seawall. I start to weave, and sea waves are in the background of my eyes. Without planning, my hand creates portraits of what I see.

For my second experience, I do the same intentionally; this time, I sit facing the trees. The two frames represent the story of the time and place that I spent making them. The frames are round, the symbol of ongoing seasons. I wove only half of the frames to say I can only see half of the things that nature is trying to teach me, and I still have a lot to learn from her.

Weaving Carpets

I think it comes from my Persian culture that when I think of craft, the first thing that comes to my mind is weaving. I grew up in the patterns of the carpets in our house, imagining gardens of flowers and roads among them. Their beautiful colors and the soft touch. Before I knew nature outdoors, I knew the patterns of gardens that were woven in our carpets. “It may be a bit of a stretch to say that every design in a rug has a deeper or hidden meaning, but we can certainly state that almost every detail in a carpet is telling us something of importance” (boftfinerugs.com). The symbols in Persian rugs may represent historical monuments, scenes from daily life, weeping willows or other trees and religious imagery such as the Tree of Life or the Garden of Paradise. For weaving, I didn’t have a complicated pattern to follow like traditional Persian weaving, but I tried to picture nature in my carpets in my own way. I used colors as symbols. I used green color on the background of khaki to picture the grass that I was sitting on in summer. For me red, green and white are the symbols of fruits, plants and sky.

I grew up in the land of carpets. Handmade carpets are an absolute part of homes. I decided to weave with confidence because I used to see weavers working a lot. But as Sennet (2008), said “you can’t understand how wine is made simply by drinking lots of it” (P. 213). The process of weaving takes so much time and is so technical. At first, I was struggling with it. So, I referred to Persian styles of weaving, and I found amazing techniques for bringing the threads back and forth to weave easier and faster. I was proud of my cultural art and craft. Weaving feels like home. You have to sit facing the loom with a soft material in your hand and lots of colors to choose from.

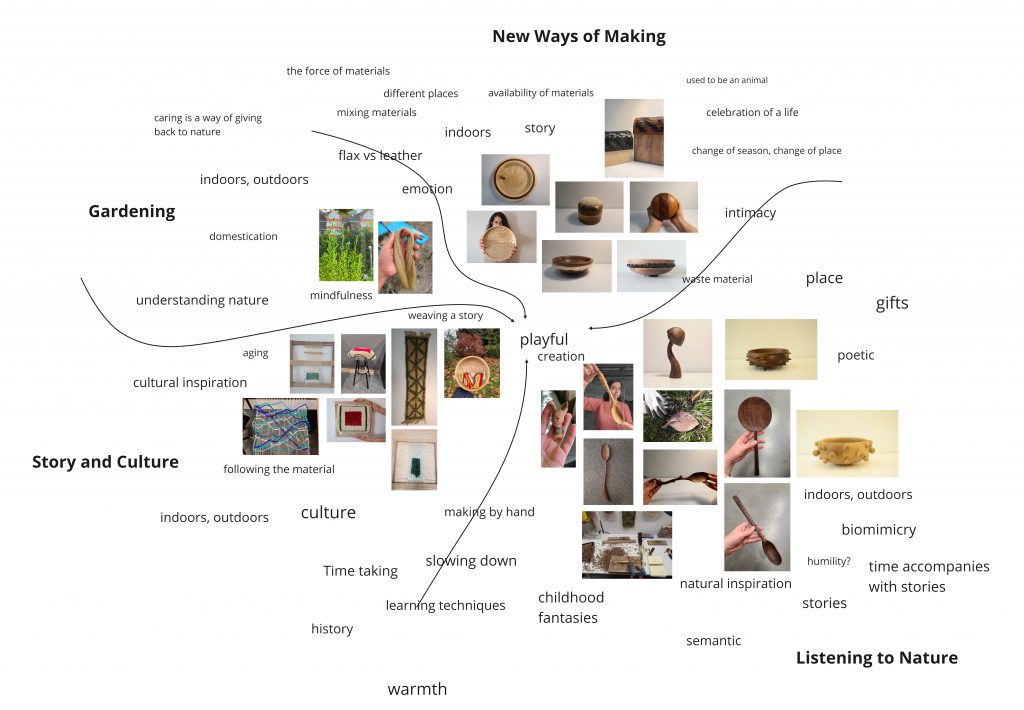

New ways of making

There are times that I play with materials, mix them, and try new things with them. Mixing leather with wood was one of them. I did it to feel better about using leather, but it became one of my favorite combinations. These two materials are adding value to each other and enhancing each other. When they sit together on an object, they both have a new character, different than when they were alone.

This combination looks so familiar. It is not the first time that wood and leather sit together. It seems like they have a history. It reminds me of old tools where someone covered the handle with a piece of leather for a more comfortable grip—each material answers to a different need. Wood represents the strength and form. On the other hand, leather has a flexible, durable, and softer character.

Participation with nature

Yanagi and Leach (2013) discussed the idea that the objects are being born, not being made. I started to think about my crafts. Are they made or being born?

Yanagi and Leach talk about beauty in imperfect things and suggest that making things imperfect makes them beautiful. It lets them be born. They say, “ The precise and perfect carries no overtones, admits of no freedom; the perfect is static and regulated, cold and hard. … There is no suggestion of the infinite” (p. 120). Their belief is so close to what Koren (2008) described about the beauty in imperfect things and in simple moments.

In the ideal condition of summer, full of free time, when even the weather was nice to me and days were generous in being long, I was sitting on the grass with a piece of wood and a knife in hand, free from any unpleasant thoughts. I was making the spoon freely. I let my hands do their job, and I was sunk in my surroundings, feeling the fresh air that I was inhaling.

Those were the moments that led to crafts being born. Pieces that are imperfect but make me feel perfect.

If I plan to make something, I usually become obsessed with wanting it to be perfect. I think of making the next versions of it to overcome the imperfection. But, with these objects, not such a thing happens in my mind. I make without planning. As a result I look at my objects, and I feel those moments. I admire the long, twisted handle of the spoon. I love the way the rough edge of the wood feels on the leaf plate.

Making far from nature

“It is autumn when Vancouver experiences its most dark and rainy days, and I spend more time indoors, making. I am wondering, how could I keep my connection with nature? I close my eyes and imagine a sunny day outside in nature, making a spoon. The green color is filling my eyes, and I am enjoying my time.

I think I can enjoy all of these beautiful and alive moments because of the rain. I should be grateful. I open my eyes, I am in my studio, and it is raining outside. I say: Thank you, rain!

I start to carve spoons. I carve a twisting form on its handle to remember the ivy. I carve a sunflower on the other to remember the mild and enjoyable sunny days, and I draw little leaves on another to remember Vancouver’s green nature. I make and send my thanks to the rain” (Sepideh Parand’s personal journal, December 2020). I think what drives me to make these kinds of forms is my internal needs. It is my heart, saying what I miss. It is a reflection of my thoughts and desires.

Gardening

I realized that I wanted to know my materials better so I decided to grow them. I did this project inside my house. I made shelves in front of my window and earned a spot for my plants to get sunlight. I used milk packages as planters.

It was my first experience planting seeds, and I was fascinated by how fast the flax seeds started to germinate. It inspired me to grow herbs and vegetables next to the flax.

At first, I was worried because I did not find a space for an outdoor garden, but now I am happy because, with this indoor garden, I can observe the process of evolving and growing my plants while living with them.

Kimmerer (2013) answers the question of how to restore relationship between land and people: “Plant a garden. It’s good for the health of the earth and it’s good for the health of people. A garden is a nursery for nurturing connection, the soil for cultivation of practical reverence” (p. 126). The connection that one can make with a plant through taking care of it is so powerful. The magical moment of my experience of gardening was the day that I saw the buds of seeds that were growing in the flaxes.

“If you let the calyxes and grasses slide through your hands amid the firefly flurries, celebrating the coming summer, you don’t just perceive a multitude of other beings—the hundred or so species of plants and countless insects that make up the meadow’s ecosystem. You also experience yourself as a part of this scene. And this is probably the most powerful effect of experiences in the natural world. When you immerse yourself in the natural world, you wander a little through the landscape of your soul” (Weber, 2020, para. 4).

Gifting

I will share warmth with gifting. What do I mean by warmth? I translate warmth as sincerity. I see a sense of warmth in my works when I want to make an artifact to give as a gift. I picture that person when I am making, and try to think about their interests and about what that person reminds me of. It gives a whimsical quality to my work. I try to show the fun and joy of creating for that person. I want the artifact to tell a story.

I receive my materials as a gift from nature and a gift from waste bins. I don’t want to be only the receiver in this cycle. One of the things that I learned from my friend tree is to give and share. “That is the fundamental nature of gifts: they move, and their value increases with their passage” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 27). I receive the gift of wood, and I pass it to others as a crafted gift.

“Gifts from the earth or from each other establish a particular relationship, an obligation of sorts to give, to receive and to reciprocate” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 25).

Reflections

Mapping the Objects

The diagram above shows most of the objects that I made. I grouped them based on the technique of making and their material: Planting; Story and Culture; Listening to Nature; New Ways of Making. My interest in learning new things pushed me to make a variety of objects. It may seem that there is no correlation between the groups of works, but when you look deeper you can find a consistency in the visual language, or a consistency in the stories underneath the objects. It is not important that they all be the same process and material. There are many threads. There is a thread between caring for nature and using leftover workshop materials that would be waste, using that material to create meaning in my artifacts. This was a way of showing respect to nature. I used what was available to me and gave them another chance to be. I received the criticism that “you have to spend a lot of time to join these small pieces of wood together to make it a proper piece to use,” but I think it is worth the time, and the preparation of the bigger block of wood became a part of my process. It is there in the story of the artifacts, too.

When I was listening to nature, my technique was mostly carving with a knife. When I use a machine for woodworking I have to plan before making, and I think that conflicts with the unpredictability of nature, which is full of surprises. Later I practiced in the same way with weaving. After gaining some experience and developing skills, I used weaving to tell stories that I was learning from the land.

Planting and growing my materials helped me to practice patience. I began to understanding how nature works by taking care of my plants.

Trying new materials and accepting all the kinds of materials that nature was offering me was a big step. In my relationship with nature I don’t choose, and I don’t take by force, but I accept what is there. I use what is being offered to me, what is available to me.

Reflective Writing

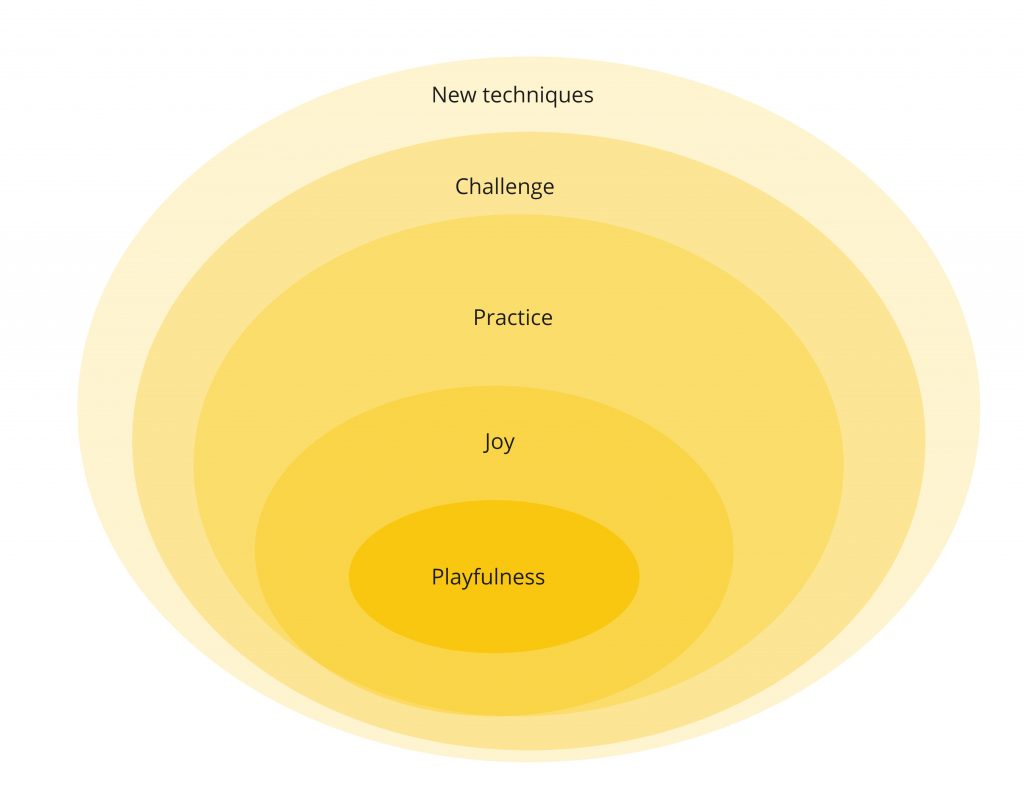

When I start each work series, my first experiences are about the technical difficulties of learning how to work with a particular material and process. That might be a little intense, and that is when most people decide if they like to continue this kind of work or not, but these challenges are fun and fruitful for me. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) talks about the happiness that arises from complete engagement in doing something. He says that optimal experiences “occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile” (p. 2). What makes one feel that way? For me it is about doing something with the sense of full productivity in learning a skill or doing a job. I think of it as a joy. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) describes this as “a sense of deep enjoyment” (p. 3). This is the feeling that I have when I am doing what interests me: making.

Csikszentmihalyi and Nakamura (2002) also talk about “The paradox of work” (p. 98), and the similarities between work and play. According to them, work is a growth activity, and play is low challenge and low skills. In both situations one can feel positive. They state that the flow state happens in somewhere between work and play; in activities that are challenging in a way that the challenge doesn’t become stressful rather than an opportunity for action. Over time, the more skilled the person becomes, more enjoyable the action will be. My practice with nature is both work and play. It is fun also requires skill. It has the power to call my soul to the deepest levels of my connection with my practice. The more I go in-depth in the making and gain experience, and the more I make, and the more playful it becomes. I find myself, lost in time and space, working with a kind of material and with a type of technique, and it is so joyful for me. That is what makes me continue.

For Sennett (2008), the hand, which develops the habitual forms of coordination and learns sensitivity through craft, is closely connected to the eye. Together there is an “extended rhythm” between them that allows the craftsman to develop specific skills and rituals, duties performed again and again. These practiced repetitions are not boring. As Csikszentmihalyi says, they are challenging one’s mind and body to do a kind of practice that requires effort and creativity in a way that brings joy and happiness.

Beauty in imperfect things

My reflection takes me to Leonard Koren’s (2008) writings about Wabi-Sabi. Koren describes the elements of Wabi-Sabi in Japanese culture and compares it with modernism. In this map I chose the elements of Wabi-Sabi that I could see in my makings.

I think I can see the small touches of Wabi-Sabi in my work. I like the idea of beauty in imperfection. I like nature and being natural and untouched. Koren says, “Beauty can be coaxed out of ugliness” (p. 51). For me, it is somehow like rewriting some believes that should be changed. It made me think about what beauty and ugliness mean to me. Like

Koren, I see the beauty in imperfection. But where I differ from Koren is when he says Wabi Sabi has a sense of sadness. I don’t know why that should be? My Wabi-Sabi is full of light and happiness. I claim this as part of my philosophy.

I also like the idea of appreciation of cosmic order. I see it when I look at the untouched knot in the wood bowl that I made. I like imperfection in my artifacts, the asymmetrical shapes. I like to see my tool marks on my material. I want to see accidental effects. Sometimes these accidents lead to a style and method, a style that represents me, or a situation, a moment in time. I don’t try to cover the joining lines in my work because I believe they tell me a story. It is the journey of materials from the waste bin to my hand, and then to the life they will have as an object.

I love when Koren says: “Wabi-Sabi suggests that beauty is a dynamic event that occurs between you and something else. Beauty can spontaneously occur at any moment, given the proper circumstances, context, or point of view. Beauty is thus an altered state of consciousness, an extraordinary moment of poetry and grace” (p. 51). Once, our teacher asked us to bring our research song to the class, the song or music that you listen to while you are working. I chose a soundtrack that I had a memory of for that assignment, but later, I recorded myself while I was carving. I watched the video; I noticed the satisfying sound of wood being carved in the video. I usually don’t listen to music while I am working. It is usually the sound that I am making, ambient sound, or sometimes podcasts and audiobooks.

The video reminded me that I listen to the wood while I am carving it. KHERCH…KHERCH… The knife is carving smoothly. KHHHH… oh, I should change my pressure or direction. In this way, we are communicating with each other. These moments are the times that poetry and grace happen between me and my carvings.

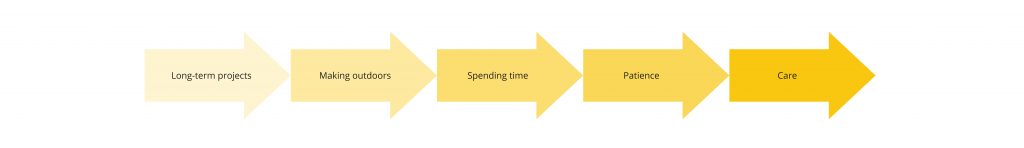

Change of season, change of place of making makes me think about long-term projects, the kind of projects where nature is a participant. I have to adapt to the pace of change in nature. I have to slow down and dissolve in its peaceful rhythm. It’s a practice of separation from modern life, which is full of fast changes and full of inputs and the challenging process of keeping up to it. It is a practice of finding peace and joy in your life. I planted flax in the summer, but I realized they are not suitable for working right now. At first, it was frustrating for me to think that I have to wait another year to plant good flax for processing and use, but this is what one learns from working with nature. The patience!

Every project requires a certain amount of time. I believe crafting needs a lot of patience. Many times, I have to start over; many times, the result is not what I expected. Sometimes I have to leave the project aside and not think about it for a while. I have to give myself time to go back to the mood to continue making. Sometimes the process takes so long that it may change through time. I believe these matters define craft and make the artifacts unique that they can carry a lot of story and emotion.

A long time ago, Illich (1929) cautioned that the new era of ever-faster speeds was taking its toll on people’s lives and the human spirit: “We are so enamored by speed, and especially by the idea of getting somewhere quickly, that our personal agency and creativity have been stunned into submission.” He saw the individual was seduced and swept up by speed and steadily being stripped of “physical, social and psychic powers” at the risk of losing his or her very center of being (Illich, 1929, cited in Strauss, 2014, p. 1). With the practice of participation with nature, what I earned was patience. The patience of crafting is an antidote to the speed of modern life.

People ask me about my favorite pieces among the thing that I have made. They ask me which one I use the most. To tell the truth, I barely use my crafts. They serve me so well during making that I usually give them away as gifts, or place them on my shelves as a treat for my eyes. Maybe I was so fascinated by the experience of creating that I have ignored the role that my crafts play in the world. Eating from a wood bowl; I can taste the wood; I can smell it. Cooking with a wooden spoon, I bet the food will taste different. I keep my tools in the box that I made with wood and leather; it feels good.

Spirituality

In my early research, I was searching for ways to encourage sustainable behaviors, and I struggled to find a way to make this education enjoyable. In time, I realized how easy it might be for others to forget this education, because consumerism is so seductive. Also, sustainable design education is forgettable because it doesn’t involve one’s heart. “Designers move quickly to try to resolve ecological problems: we develop apps that support Citizen Science, script virtual reality immersive experiences to incite empathy, create new materials from bark, or invent novel ways of using so-called waste” (St. Pierre 2020, p. 5). These designers are trying to address sustainability at the level of problem solving. They need their hearts engaged, like a true belief, like a way of living. On a spiritual path, one can find spirituality in the way one lives. Gottlieb (2013) says, “Spirituality is an understanding of how life should be lived and an attempt to live that way” (p. 5). I try to engage this belief in my day-to-day life like a ritual that involves practices in relation to nature.

Kimmerer describes the difference between sustainable development and spirituality in a story where she tried to explain sustainable development to one of her elders. That person replied, “This sustainable development sounds to me like they just want to be able to keep on taking like they always have. It’s always about taking. You go there and tell them that in our way, our first thoughts are not ‘what can we take?’ but’ What can we give to Mother Earth?’ That’s how it’s supposed to be” (p. 190). It is like the earliest lessons that we learn as a child; when someone gave you a gift, take it, be grateful and find a way to reciprocate. A spiritual connection with nature is when humans can live in symmetry with nature.

St. Pierre found her reciprocity in the everyday practice of meditation. She says, “ [the] practice of Buddhist ethics … arises from day-to-day exchanges of my life and my meditation practice” (St. Pierre, 2020, p. 7). I found it in making. Ever since I started carving spoons, I found myself making them when I need to calm down. I found myself carving as an act of therapy for my soul. Carving is so different from other practices because I can let my hand do the making and my mind is free of everything. I am just the observer of the process of the wood that is getting shaped. I have a stack of wood that I have collected from the waste bin over time. I don’t know where the wood came from, but I feel a sense of responsibility to use these pieces again. That’s why I continue making with them. This is a day-to-day practice

for me.

Once, someone asked me, “when you take material from nature, how you give back to nature?” I was struggling for a time to find my big gesture in return to the generosity of nature. I found a beautiful answer from Kimmerer (2013) that says in return to the gifts that we receive from nature, gratitude is enough.

Some might ask, is gratitude enough? To answer this question, I should explain how I understand gratitude. How do we live in gratitude? Gratitude is paying attention to the gifts that the earth gives us. It is paying attention to the plants and other beings. There is a spiritual sensibility in gratitude that we should be very aware of. Real gratitude can change the way we behave and live. It comes with responsibilities to the land. Gratitude shouldn’t be mistaken as a form of acting, but it is a way of being. “Cultures of gratitude must also be the culture of reciprocity. Each person, human or not, is bound to every other in a reciprocal relationship. Just as all beings have a duty to me, I have a duty to them. If an animal gives its life to feed me, I am, in turn, bound to support its life” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 115). Practicing

the language of animacy, opening to the agency of materials and learning from the non-human world are the ways to understand the real place of humans in the natural world.

We are next to each other. These practices helped me to understand my duties to the world and helped me to learn reciprocity to show my real gratitude for the gifts that the nature is giving me. When I am carving the wood, I am grateful for the gift that the tree gives me. I feel a connection with it, and by spending time with it, I am practicing gratitude. When I forget about it, I have people to remind me. As I was carving the other day, impatient, I heard Kimmerer’s voice, “Slow down. It’s thirty years of a tree’s life you’ve got in your hands there. Don’t you owe it a few minutes to think about what you’ll do with it?” (Kimmerer, 2013, p. 155).

The other way of showing gratitude that I learned is giving gifts to nature. Kuokkanen (2006) talks about gift practices in indigenous peoples’ philosophies. They use gifts as a way to give back in their ceremonies and rituals “to acknowledge and renew the sense of kinship and coexistence with the world” (p. 256). This act shows their gratitude for the gifts and abundance of the land. Giving gifts to the land is a human way of remembrance and establishing reciprocity: “the gift is the manifestation of reciprocity with the natural environment reflecting the bond of dependence and respect toward the natural world” (p. 258). It is a beautiful act of giving a gift to the mother earth to say thanks for her gifts and her generosity.

Summary Reflections

In this journey I lived what I read in theory. It was a praxis of art, design and, theory. This project is more than a Master’s thesis for me. It is a way of life. It doesn’t finish with my education, but it will stay with me, and I will share the story of how I saw nature differently and how I could talk to her.

I was a maker and craft person long before my Master’s studies. What changed now? In a recent webinar Kimmerer was asked to define an educated person. She replied that “an educated person knows their gifts and where to give them in the world” (Kimmerer, 2021).

After my journey to find the relationship between me, my craft, and nature, I think it is time for me to offer my perspective of how another person could use this way to get closer to the land and use its spiritual gifts.

Find a place in nature

In this step, first find a place in nature. This place can be far away from your home or in a short walk away. It can be different for each person; someone may find feelings of resonance in the park next to their home and, someone can find it in a faraway place. But get out of your home and into nature. Camozzi (2019) says we should seek the unfamiliar, but to me, it can be the same place in nature, again and again.

Find your ritual

The main reason I chose craft as a way to make a connection with nature was that it is my way of finding peace within me. I developed a practice of crafting that I can stick to because I love it. I relax when I make something while I enjoy the gifts of nature. It may be different for each person, so I suggest that each person develop their own practices. It can be walking, writing, reading, painting, exercising, and so on. The main thing that I am trying to say is that it is not a fixed practice that one does to reach some sort of abstract goal, but it is a way of being and connecting.

Do it regularly

As Blenkinsop & Beeman (2010) mention “A strong, ongoing relationship with other- than-human world is necessary for the co-teaching to go well” (p. 38). This is going to happen over time with day-to-day time spending with nature. In each visit with nature one can learn new things. Over time one can learn ways to interact with nature. The first visits

were a little awkward for me. Of course, I was full of wonder and excitement, but I wasn’t sure how to talk to nature, how to listen to her, where to go, where to sit, and what to look for. In time I learned my ways, I built a relationship with nature. We are becoming like old friends.

Do it alone or with friends with the same intentions.

I think it is important to keep your practice sacred without distraction from others or from the fast speed world. This is the time to forget about concerns and just be there, sitting in nature and soaking in her peace. When you find others with the same intentions as yours, you can share your knowledge and experiences with them. You can see other aspects of your ritual in a fresh way.

Find time to reflect.

Reflect on the positive energies that you got from nature. Ask yourself questions. Remember what you learned and how you felt. Keep refining this practice so that it works for you, in order to find your place in nature.

In the end, I wish for a better tomorrow with more individuals involved in thinking about and working toward making a relationship based on reciprocity with our endearing nature.

I believe individuals are a part of society, and a change in one’s beliefs and behaviors can make a significant change.

I am doing my share by finding a deeper connection with more-than-humans and the Earth through the practice of land-based making and finding my place in nature.

Works Cited

- Bertolotti, E. et al. (2016). The Pearl Diver: the Designer as Storyteller. DESIS Network Association.

- Blenkinsop, S. Beeman, C. (September 2010). The world as co-teacher: Learning to work with a peerless colleague.

- Camozzi, Z. (2019). “Earthbond Protyping, a Method for Designers to Deepen Connection to Nature.” In Design and Nature: A Partnership, edited by Fletcher, K., St. Pierre, L., Tham, M. London Routledge. Pp. 146-152.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Harper and Row. (1990). FLOW: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. https://earthand.com/

- Fletcher, K. St. Pierre, L. Tham, M. (2019). Design and Nature: A Partnership. Routledge, UK.

- Fletcher, K. (2021). Life Writing as an Ecological Research Method. Fashion Practice, DOI: 10.1080/17569370.2021.1882760

- Holroyd, A. T. (2013). Folk Fashion: Amateur Re-Knitting as a Strategy for Sustainability. Birmingham Institute of Art & Design. Birmingham City University.

- Ingold, T. (2010). The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics.

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2021, January 29). A Conversation with Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer [Webinar]. University of British Colombia.

- Koren, L. (2008). Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. Illustrated, Imperfect Publishing.

- Kuokkanen, R. (2006). The Logic of the Gift: Reclaiming Indgenous People’s Philosophies. In Re-Ethnicizing the Minds: Cultural Revival in Contemporary Thought, edited by Thorsten Botz-Bornstein and Jürgen Hengelbrock, 251–71. Studien Zur Interkulturellen Philosophi Amsterdam: RODOPI

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

- Mackinnon, A. (1996). Learning to teach at the elbows: the Tao of teaching. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada.

- Mathews, A. S. (2019). Coming into noticing on being called to account by ancient trees. University of Calgary Press.

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. Handbook of positive psychology, 89-105.

- Niedderer, K. Townsend, K. (2009). Craft Research: Joining Emotion and Knowledge. University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.org

- https://www.ofsedgeandsalt.com/

- Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman. Yale University Press.

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation.

- St. Pierre, L. (2020). Baskets of Offerings: Design, Nature, animism and pedagogy, Extract from Dissertation Taking a Contemplative Turn in Design.

- St. Pierre, L. (2015). Engaged Sustainable Design: Creating moral Agency. Nordes 1 (6). http://www.nordes.org/opj/index.php/n13/article/view/381.

- Strauss, C. (2014). Speed. Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion.

- Stuckey, P. (2010). Being Known by a Birch Tree: Animist Refigurings of Western Epistemology. Prescott College.

- Weber, A. (2020, September 16). What the Meadow Teaches Us. Retrieved September 17, 2020, from Nautilus website: http://nautil.us/issue/90/something-green/what-the-meadowteaches-us-rp

- Yanagi, S. Leach, B. (2013). Unknown Craftsman: a Japanese Insight into Beauty. Kodansha USA.